Turkey is not short of ambition when it comes to infrastructure projects. In October 2018, it opened the world’s largest airport (‘Istanbul Airport’). 2016 saw the unveiling of the world’s widest suspension bridge which links Asia to Europe across the Bosporus Strait. Turkey also plans to build a 45km shipping canal running parallel to the Bosporus to rival the Panama and Suez Canals.

According to the Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources, Turkey ranks only behind China in its thirst for energy. Energy demand has grown 7 percent annually from 1990 until today. Despite an 80 percent increase in electricity generation in the past decade – including a 90 percent growth in renewable capacity – Turkey is still struggling to meet its electricity generation needs.

Turkey is also battling to reduce its dependence on $55 billion of fossil fuel imports which account for 77.5 percent of its energy needs. Natural gas from Russia and coal from various foreign sources add up to 1.5 times the size of Turkey’s overall current account deficit, pointing to a pressing, long-term economic vulnerability.

To its credit, renewables feature prominently in Turkey’s road to energy independence. Earlier this year, Turkey announced a bidding process for the largest offshore wind farm in the world. The estimated $2 billion offshore plant will have a capacity of 1,200 MW – roughly twice the capacity of the record-holding London Array – and will be located either in the Aegean, Marmara or Black seas.

Meanwhile, Turkey plans to hold four 250 MW wind energy tenders by the end of this year for four plants with an investment volume of around $1 billion. This follows a 1,000 MW tender held last year which resulted in a world record feed-in-tariff of $3.48 per kilowatt-hour (kWh) offered by the Siemens-Türkerler-Kalyon consortium, highlighting the competitiveness of Turkey’s wind energy sector.

With the second biggest solar potential in Europe behind Spain, Turkey has impressive goals for PV capacity as well. The Turkish solar energy association, Günder, predicts that PV could reach a cumulative capacity of 14GW by 2023. This seems a steep hill to climb since Turkey is starting from an installed base of the only 5GW. However, the country added 2.5GW solar capacity in 2016-2017; it held a 1GW solar auction in 2017; and it announced a 100-day energy action plan this August, which included the goal of 3GW in solar tenders worth $4.8 billion in investment.

Government-sponsored projects aside, the vast majority of solar capacity has come from so-called unlicensed projects – those less than 1MW which are not the result of a competitive tender process. Private players like Akfen Renewable Energies are also taking the country’s renewables destiny into their own hands. The company has secured a $363 million from the EBRD, Germany’s KfW IPEX-Bank, and a series of Turkish banks to build nine new solar plants with a cumulative capacity of 85MW and four wind farms totaling 242MW.

This is all part of Turkey’s goal to produce 50 percent of its electricity from clean sources by 2023. As of August 2018, Turkey hit 31 percent renewable electricity production. However, this is only 3 percent higher than the 2013 figure, suggesting that the 50 percent target will take much longer to achieve.

Renewables’ Intermittency Makes Coal A Necessity

A key barrier to reaching an energy mix with 50% renewables is the cost of managing intermittency. Scientists have estimated that when intermittent sources reach 20-30% of the energy mix, balancing costs can add 30-50 percent to the cost of renewable energy installations themselves[1].

Therefore, there will be a need for non-intermittent energy sources – whether fossil fuel, nuclear or hydroelectric – until energy storage costs decrease significantly. In Turkey’s case, it has also more or less exhausted its hydroelectric generating capacities and it is not richly endowed with oil or natural gas. Turkey is planning to build three nuclear power plants, targeted to generate 15 percent of its electricity production, but these will not be ready until at least 2030.

And so, in the short-term, it seems that Turkey has little choice but to invest heavily in its only domestic energy source – coal. The Afşin-Elbistan power plant in the Elbistan district of Kahramanmaraş in southern Turkey is expected to become the biggest coal-fired power plant in the world and there are 80 new coal power plants in the pipeline – equivalent to the capacity of the United Kingdom’s entire power sector. Only India and China, which have much larger populations, match Turkey in predicted growth of coal production.

Turkey already imports nearly 40 million mt of coal annually from locations such as the United States, China, and Australia. Imported coal typically has a 20-30 percent higher calorific value than Turkish varieties. Therefore, in order to make domestic coal more competitive, it is heavily subsidized. Coal projects routinely receive free state land, exemptions from corporate taxes and tariffs, a 50 percent discount on electricity bills, and state funding for wages, insurance premiums and interest on investment loans.

To add to its sustainable energy challenge, Turkey’s recent economic woes may further curtail renewables development. The lira has declined steeply in 2018 and is likely to put off foreign investors who are crucial for the development of the sector. State-owned grid operator TEIAŞ reported just 18MW of new unlicensed PV capacity in July; by comparison, there was 1.1GW of new capacity in the first few months of the year. The government has authorized foreign-currency loans for approved unlicensed PV projects of up to 1 MW. However, if currency volatility remains that may not be enough to stave off falling foreign investment and may push the goals of the ambitious renewable projects out of reach.

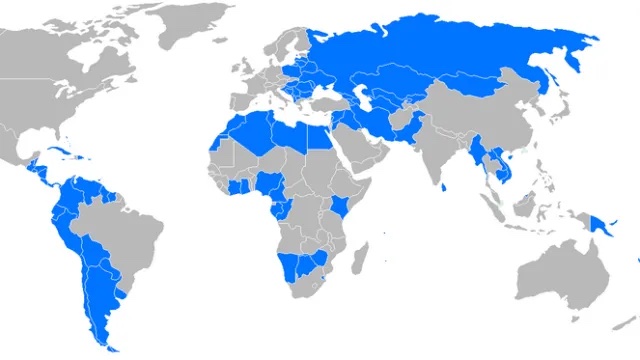

Turkey is emblematic of a wider conundrum faced by many emerging economies. Even when governments wish to transition towards renewables, they may still have to deploy dirty energy sources such as coal to tackle the intermittency issues. For example, Asian coal consumption grew by 3.1 percent a year from 2006 to 2016, accounting for almost three-quarters of the world’s demand. India, a signatory of the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, consumed an extra 27 million tons of coal in 2017, an increase of 4.8 percent, which helped push up global coal consumption for the first time in four years.

[1] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0306261918300230

This piece was co-authored by Matthias Lomas in London.

Photo Credit: Yavuz Sultan Selim Bridge, Turkey Discover The Potential